Wrangling Limericks using Scrapy

Overview

I mentioned in my last post, on using RNNs to write poetry, that I got the poetry data by using Scrapy to scrape various poetry sites. I also mentioned that I would try to write a blog post giving more specific details about how I did this. So in an effort to not have our relationship built on foundation of lies I decided to try to follow through on this promise. Specifically, I'll talk you through how I collected a bunch of limericks from OEDILF. In case you weren't already aware OEDILF is an community of people with the unbelievably ambitious goal of creating a limerick for each word of the English language. Anyway, Hopefully after reading this post you will have an idea of how to sift through website API and design a spider to extract your own data.

Before we delve any deeper I should let you know that if you are completely unfamiliar with XML and XPath then this will probably look like Greek. If that is the case I would recommend checking out this XPath tutorial before going any further.

Getting started

The first step for data scraping, perhaps counterintuitively, is to decide what you want your final product to look like. It's possible that your desired final product will change a bit as you start designing, but having a rough idea of what you want the output to look like can help you design your spider. For example, maybe you are interested in baseball games played by your favorite team. In this case you might want the final product to be a table where each row is a game and the columns are pieces of info about the games (i.e. what was the score, was your team home or away, what was the attendance, was it a day or night game, etc.) In our case, we are interested in getting a big list of limericks and so the final structure of our data should be a table where each row is a limerick and there is a single column that contains the text of the limerick. Now that we know what we want our data to look like lets build a spider to collect it.

If you want to follow along on your own machine you will have to install Scrapy. Instructions for this can be found here. In order to start your own scrapy project you can just type

$ scrapy startproject yourProjectName

This will create a new project called yourProjectName in whatever file you are currently in that contains all the necessary pieces to start building spiders. Next, navigate inside this directory to yourProjectName/spiders and create a spider file your_spider.py (or whatever you want to call it.)

What is a spider

Before going any further we should talk about what a spider is and how it goes about collecting data. A spider is a Python class with methods that allow it to navigate and extract data from websites. Here is the beginnings of the spider I used to collect the limericks

import scrapy

import re # for using regular expressions

class LimerickItem(scrapy.Item):

# define the fields for your item here like:

limerick=scrapy.Field()

class LimerickSpider(scrapy.Spider): # a spider for scraping limericks

name = "limerick"

start_urls = ['http://www.oedilf.com/db/Lim.php?Show=Authors']

allowed_domains = ["oedilf.com"]

def parse(self,response):

#code telling your spider how to navigate the page

The LimerickItem class is the object that will store the data that we scrape. You should think of an instance of this class as a dictionary where the fields are the keys for the dictionary. You'll see how this analogy plays out later on. The LimerickSpider class is our spider. It has three important attributes: its name (pretty self explanatory), start_urls which is a list of urls that our spider will start its crawls from, and allowed_domains which restricts the pages our spider can crawl on (this last attribute is not strictly necessary, but it helps keep our spider from running amuck). There is also an important method for our spider and that is the parse method. This method tells the spider how to navigate the website and what it should store in the item fields. Basically, this method makes a request to an element of start_urls and is given a response from the website. The response is given as the XML code for the page requested. We'll talk more about it in a bit after we get a clearer idea how the data we want is structured on the website.

Inspecting the website

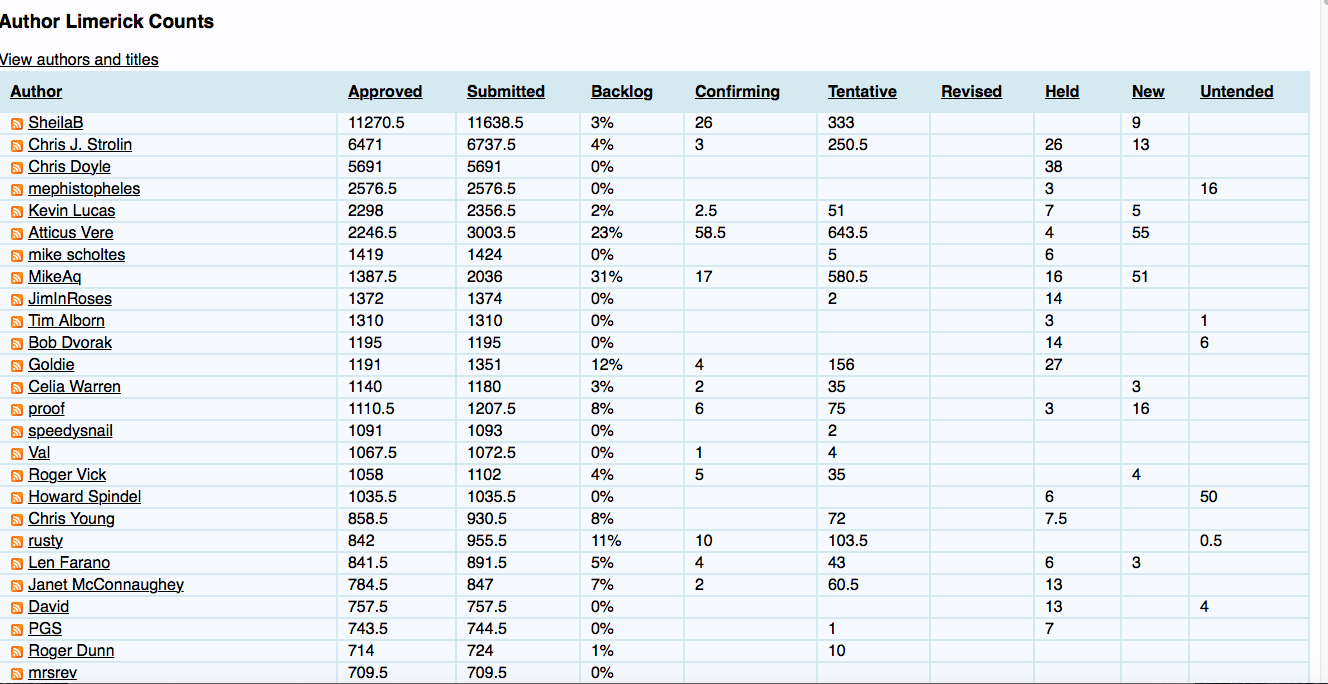

Let's take a minute to see how the limericks are organized on the OEDILF webpage. If you navigate to the OEDILF author page you will see a big list of users who have posted limericks to the site.

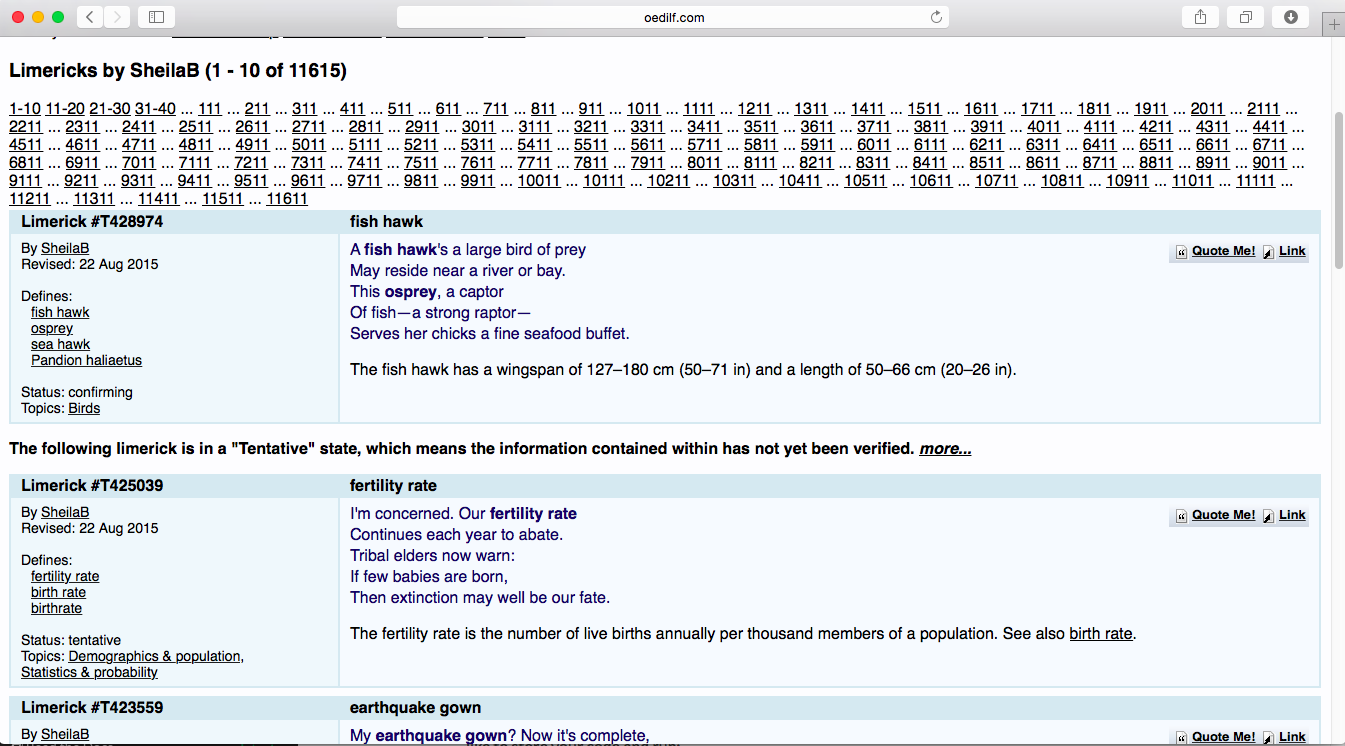

As you see there are several authors here and each of their names is a link to a page containing (a subset of) their limericks. If we click on one of the author's names (say, SheilaB) we see that it links us a page with their first 10 limericks. If the author has written more than 10 limericks then the top of the page there will be other links to similar pages with their other limericks.

So at this point, we see that our scrape will have three steps.

- Compile a list of author urls

- For each author, navigate to their page and figure out all of the urls for their limericks

- Navigate to each of these pages from step 2. and extract all of their limericks.

Transitioning from one step to another involves navigating to a new page. As a result the spider we build will have 3 separate parse methods, each of which deals with one of the above steps.

The code

1. Collect author urls

Here is the code for the parse method that collects the author urls

def parse(self,response): #first get the links for each author

items=[]

l=response.xpath('.//a[@title="RSS feed"]/@href').extract() # the ones who have actually posted a limericks has an RSS feed

author_ids=[]

for item in l:

author_ids.append(item[12:-7]) #this is the id number from the url

author_urls=[]

for aid in author_ids:

author_urls.append('http://www.oedilf.com/db/Lim.php?AuthorId='+ aid)

for link in author_urls:

request=scrapy.Request(link,callback=self.parse_layer2)

yield request

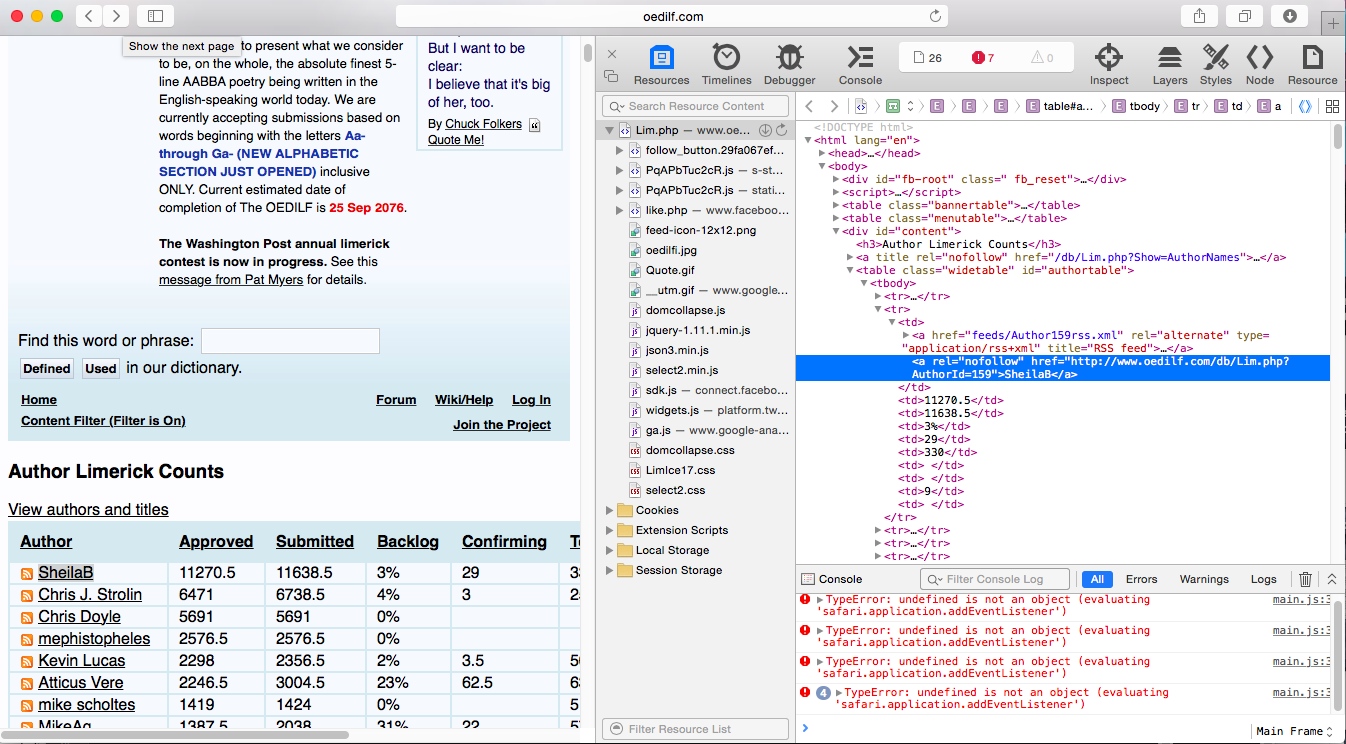

Here is what is going on. We know we are looking for a link, but there are lots of links on the page and so we want a way for XPath to focus on the ones we want and ignore the rest. Here the inspect element tool is really invaluable. If you go to one of the links and right click you will see the inspect element option (I am using Safari, but this should work in other browsers). When I do this the DOM file for the website will open and the element I clicked on will be highlighted in the DOM.

After doing this we see url for our author. If you scroll down the list, you will notice that there are lots of authors on the list who are slackers that have not actually contributed any limericks. We want to ignore them, and thankfully these lazy authors have not been rewarded with an RSS feed (indicated by that little logo that you see to the left of SheilaB's name). Thus using the code l=response.xpath('.//a[@title="RSS feed"]/@href').extract() we get a list of the id numbers for all of the authors who have submitted a limerick. The next few lines are just standard python that turn these id numbers into the urls for the authors page (I realize that this part is stupidly implemented, but it works and I'm too lazy to fix it right now). The last two lines are a bit less trivial. This is the part that allows us to navigate to the authors page and move on to step 2. Let's take a more detailed look at the line

request=scrapy.Request(link,callback=self.parse_layer2)

This line makes a request to link and feeds the result in to the callback function (that we will define in a moment). The last line of the code then yields the result, which as we will see is a bunch of LimerickItems instances each of which contains a single limerick. In fancy python speak this means that our parse function is not actually a function, but a generator (for a nice intro to generators you can look here).

2. Collect limerick page url's for each author

Next, we talk about the parse_layer2 method. Here is the code

def parse_layer2(self,response): # this layer figures out how many limericks the author has

try:

last=response.xpath('.//div[@id="content"]/a/@href')[-1].extract() #this almost (+- 10) of the number of limericks the author has written

m=re.search('Start=.*',last)

bound=int(m.group()[6:])

except IndexError:

bound=1

ix=0

while ix<=bound:

link=response.url+'&Start=' +str(ix) #each of these pages has <=10 limericks

request=scrapy.Request(link,callback=self.parse_layer3)

ix+=10

yield request

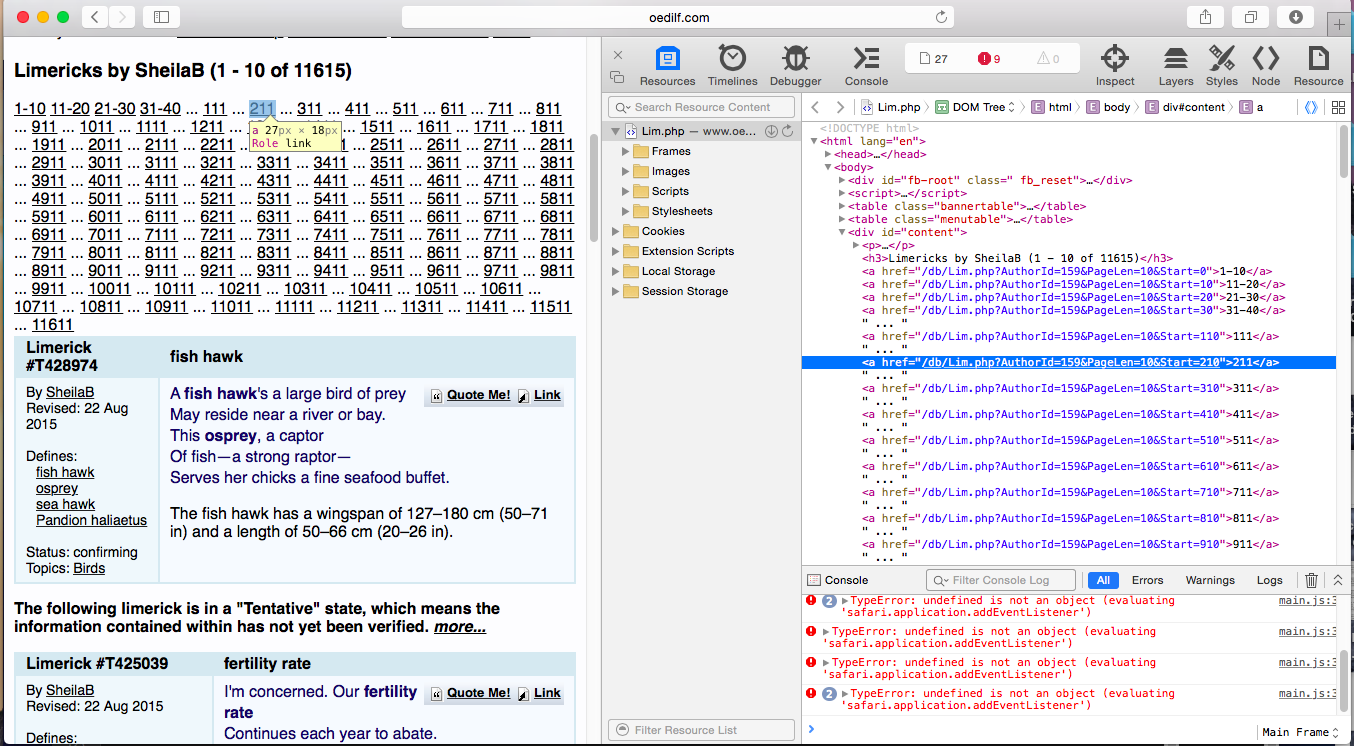

This portion of the code looks at all of the links on the top of an author page and figures out how many limericks they have written. Fortunately, this website has pretty good API and if we inspect one of the links at the top of the page we see that its url is of the form

http://www.oedilf.com/db/Lim.php?AuthorId=159&PageLen=10&Start=210

If we replace 210 with another multiple of 10 we will get another list of limericks (provided there are that many limericks). This means that we just have to figure out how many limericks there and then iterate over urls of this form and feed them into another request, and that is exactly what the code above does. Finally, after another request/yield combo we can move on to. . .

3. Extract the limericks.

This is actually the easiest part and so I won't say too much about it. Here is the code for the third parse method.

def parse_layer3(self,response): #navigate to the limericks page and extract the limericks on the page

items=[]

lims=response.xpath('.//div[@id="content"]//div[@class="limerickverse"]')# the limericks on the page

for lim in lims:#format each limerick as an ascii string

item=LimerickItem()

s=lim.xpath('./node()').extract()

t=strip_list(s)

t=t.encode('ascii','replace').lower()+'\r\n'

item['limerick']=t

items.append(item)

return items

Using the inspect element command again we see that the limericks are divs of class limerickverse inside the div whose id is content. Inside the loop you should notice that we finally create an instance of our LimerickItem class. Most of the code in the loop is just processing the limericks. As you can see, the syntax for adding stuff to the our LimerickItem is just like a python dictionary. By the time the loop finishes we will have an items list of instances of LimerickItem each of which contains the text of a limerick.

Testing out your spider

So now you have seen the inner workings of a spider and are probably armed with the knowledge to begin writing your own spider to turn loose on the internet. Before you do, its a good idea to make sure that your spider is in proper working order. Fortunately, Scrapy makes this testing nice and easy. Using the Scrapy shell you can do all sorts of testing to see how your spider interacts with the page you are trying to scrape and to make sure that your XPath code is doing what you want. I won't go into too much detail since the Scrapy people have already put together this nice tutorial.

Crawl, baby, crawl

Now that you have written your spider and tested it out, its time to take it out for a test drive. Like everything else, this is a cinch. Let's say your spider's name is mySpider and you want it to crawl and then dump its data to the file data.csv you cd to the spider's directory and run the command

$ scrapy crawl mySpider -o data.csv -t csv

If csv is not your cup of tea and your data structure of choice is JSON you can make the obvious changes to the above line and have your spider dump the data to a JSON file. There is also support for a couple of other data structures, but I don't remember all of them off the top of my head.

Final thoughts

Hopefully this post has shown you how flexible and powerful a tool scrapy is for wrangling pretty much any type of data. Basically, any type of data out there on the internet is at your fingertips. However, as we all know, with great power comes great responsibility, and so it is important to use this tool with some discretion. Your spider moves very fast and is capable of making a lot of requests to a website. If you aren't careful, this can cause their server to get bogged down. If this happens it will likely make the webmaster pretty mad and possibly get you banned from the site. There are various ways to avoid this, such as throttling back your spider or even contacting the site in question before deploying your spider. For more information about crawling best practices check out the Scrapy site

Also, before taking a lot of time writing a spider to get your data it is worth looking into whether the website you are interested in has an existing API for requesting data from them. Twitter and GitHub are prime examples of sites with well developed API for requesting data.

If much of this was kind of confusing there is a good chance that it was my fault, but never fear as there are some other nice resources out there on how to scrape the web. You could take a look at Jay Feng's blog post that uses Scrapy to get apartment listings from Craigslist or Greg Reda's post on scraping Chicago Reader's Best Lists

If anyone builds any cool or clever spiders or scrapes some interesting data I would love to hear about it. Happy Scraping!!!